It was great to see a large attendance at the Australian Basic Income Lab event a few days ago at Macquarie University, featuring UK scholar Joe Chrisp on the politics of basic income in UK and Finland. Chrisp’s insightful presentation touched on the practical political meaning of the term “basic income”. The point I took away is that while “basic income” can refer to a specific policy, archetypically some form of UBI, the movement is rather fluid and context dependent. In practice, the “basic income movement” is functioning as a vehicle for advancing certain goals for the welfare state:

- cash over paternalistic benefits such as food stamps and basics cards (cash)

- repealing conditionality instead of hoop jumping (unconditionality)

- universalism over means testing (universalism)

- a social and humanitarian right to a minimum standard of living (basic minimum)

- a concept of “social rights” provided by the state to individuals, unmediated by other social structures like family or charity (individual right).

I subscribe to all of these principles, and hope they serve as a compass for the future of the welfare state. In that spirit I’m pleased to be associated with the Australian Basic Income Lab as a Fellow. As goes without saying, the following are my personal views on welfare state and basic income discourse and do not reflect anyone else’s.

I generally view my welfare politics as embracing the universalistic, egalitarian and socialistic principles that Esping-Andersen famously called the “social democratic” model. There is considerable overlap between this agenda and goals of the basic income movement.

I do not place a high priority on consolidating the welfare state down to a single omnibus payment – a UBI – or, in the present context, on moving to a post-materialist politics that displaces the centrality of market labour for most people of working age. I do agree with the movement that work should not be valued for its own sake, and that governments should move away from a fixation with coercing people into labour. That said, governments should promote full employment policy, which helps unemployed and low status workers achieve greater social mobility and greater security, while also increasing output, promoting worker power and containing welfare costs. That cost control helps us expand the quality of benefits, closer to a functional, de facto basic income.

Building a better welfare state

I see the most likely pathway to a de facto basic income – I’ll call it functional basic income – in building up an encompassing web of universalistic welfare state institutions, providing salient benefits for Australians across the income and class spectrum. I see increasing the quality and coverage of categorical welfare benefits (age, disability, unemployment etc) as a more useful approach than attempting to leapfrog the welfare state building process with a single omnibus payment, a sort of UBI half-way house. I can see the attraction of it, and respect people who advance discourse with these ideas. But I also think there is a risk it could end up doubling down on the most iconic weaknesses of the Australian system: kludgey and inefficient means testing, and relatedly, extreme familialisation – that is, outsourcing responsibility for social risks to partners and family, rather than as an individual right. That dynamic forces people into degrading and often patriarchal relationships of dependence, while failing to recognise the reality that modern Australian households regularly rely on two incomes. As these families become more common, there is falling share of Australian workers with unemployment protection. Australia’s complete absence of any individual-level unemployment protection is not the norm, and changing this should be a priority.

Barriers to a single UBI

A UBI is a logical maximisation of all the aforementioned basic income principles. However, a liveable UBI in the context of, say, present-day Australia would involve implausibly large transformations to the tax-transfer system – in particular massive and unprecedented hikes in taxation. The main driver is providing a benefit to people of working age, including full-time workers. The expenditure would be a few to several hundred billion dollars, depending on the model, for people who mostly have their income needs covered by wages.

A UBI would also extend payments to people not in the labour force (NILF) for discretionary reasons – such as early retirees, vacationers and stay-at-home spouses who are not engaged in caring labour (caring labour would be a case for public support). These groups of discretionary NILFs are basically absent from public discourse, but collectively there is far more of them than the unemployed. They have left the labour market for private benefits – of themselves or their partner. I don’t have any moral problem with these decisions, but it seems reasonable for them to be privately funded.

Most of the Australian activist welfare focus is on the JobSeeker Payment, which makes sense as the payment is too low and mutual obligations are unreasonable and frankly abusive in their current form. Mutual obligations introduced by Howard and subsequently expanded must be repealed as a top priority. But the solution to an onerous and coercive unemployment benefit is to remove what’s onerous and coercive. This does not have to be a UBI.

Frustratingly, unemployment is the hardest welfare category to make strictly universal and unconditional. All other welfare categories – children, old people, disabilities, etc – are contained groups of people relatively unlikely to work, and the inherent boundaries around these groups means that eliminating means testing and conditionality will only increase expenditure so far.

The boundaries around unemployment (or underemployment) are more fuzzy. They include insufficient working hours (i.e. low income) and active participation in the labour market (i.e. job search). Unemployment is thus very close to being defined by low income and job search. (You could test hours of work instead of income, but I think that’s worse.) The income test separates the hundreds of thousands of significantly underutilised people from the more than 13 million workers who are not; the activity test separates them from the discretionary NILFs: early retirees, stay-at-home partners etc. Eliminate means testing and conditionality and you have literally every adult, a full UBI. Back of envelope: at pension level that’s around $550 billion, plus around $45 billion for a children’s benefit at a 30% rate. Removing the existing welfare payments, the total is around $450 billion. That would require increasing taxes by around 85%.

We’d move from a lowish taxation country to the top pack, around Sweden and Belgium. We’d out-tax Finland and Norway, but sit just below Denmark and France – the top taxers. All just for a UBI, without the spending mix that underpins cross-class public tolerance of taxation even in these countries with a history of big government. (That spending mix is gigantic contributory schemes, and expansive public services, such as free or cheap healthcare, childcare and university.) We’d have top tier taxes without any needed extra spending on climate change, health technology, infrastructure or the ageing population.

UBI looks extremely unlikely, barring a black swan upheaval in technology or societal organisation.

Towards a model

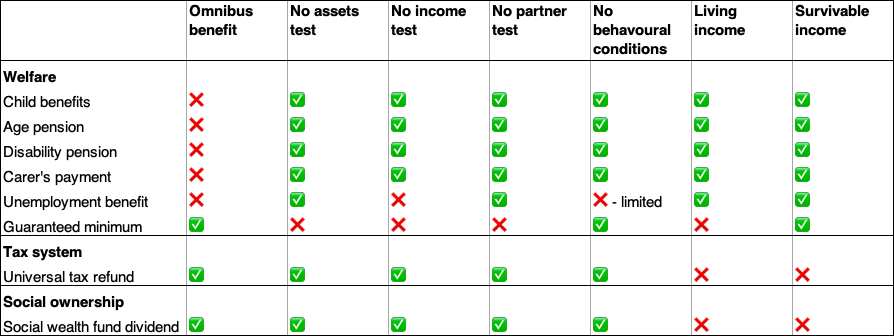

Does this mean abandoning the goals of basic income – cash, unconditionality, universalism, a basic minimum and welfare as an individual right? No, but they must be delivered at the system level, through a multilayered web of payments, with different goals being delivered in different parts of the system.

The system I envisage is something like the following.

The JobSeeker Payment would be replaced with two separate benefits: an unemployment benefit and a guaranteed minimum benefit. The unemployment benefit would largely repeal means testing, but maintain some conditionality. The guaranteed minimum benefit would abolish conditionality but maintain tight means testing.

The unemployment benefit would be set at pension level. It provides individual level protection for workers who lose their jobs and wish to continue their engagement in the labour market. It maintains individual income testing but eliminates assets testing or partner income testing. Job search requirements are scaled down to something more akin to the system prior to the mid-1990s. We might consider something like this: attend meetings at 6 and 12 months to discuss job search strategy, with an expectation of applying or interviewing for 2-4 jobs per fortnight but with minimal monitoring for the first 6-12 months, and gentle scrutiny thereafter. The Job Network would be dismantled and replaced by a resurrected Commonwealth Employment Services to reduce perverse incentives. For long-term unemployed, optional subsidised work options would exist. These would be similar to the Keating-era Job Compact (mum got one of these jobs and it was great) but the subsidy would taper down over years not months to reduce incentives for employers to game the system.

The guaranteed minimum, a separate payment, would exist to serve one purpose: a human right to avoid extreme poverty. It would be below pension level and cover a person’s accommodation costs, capped at the rate of a room in share accommodation in their area, plus a small allowance. It would be a last resort payment, and tightly means tested against personal and partner income and assets, including home ownership. This is to avoid funding early retirees and middle-class stay-at-home partners, though they could obtain the unemployment benefit with labour market entry.

Generally able-bodied people of working age who voluntarily exit the labour market would be expected to finance themselves, but there is a standard below which we should permit no one to slip regardless of their circumstances or choices.

Dividing the current unemployment benefit into two – one specialising in universalism, the other unconditionality – is influenced by the European distinction between social insurance and social assistance and, as I see it, the only practically feasible way to achieve both goals in an unemployment context.

In summary, my welfare model would include the following:

- Universal and unconditional child benefit

-increased to cost of child at relative poverty line - Universal and unconditional age pension

-offset through elimination of superannuation tax concessions and replacing asset test with gentle wealth or inheritance tax - Universal disability and carer’s benefits

- Unemployment benefit without assets or partner income test, but with income test and soft conditionality

-increased to pension level - Unconditional but tightly means tested guaranteed minimum income.

There would also be single parent and student benefits, but I don’t have settled thoughts on how these would work.

Universal dividends and market socialism

Welfare benefits aren’t the only reason for cash transfers. A national wealth fund should be established to provide equal dividend payments to all citizens. This is the centrepiece of my market socialism, and the most plausible way forward for socialising ownership and redistributing capital income at scale. Such an arrangement would take a slice of passive income currently enjoyed only by capitalists, who are able to earn rents off the commons and the stock of accumulated societal knowledge and infrastructure. A universal dividend would allow low income people to capture the equity-risk premium, so important for wealth of the top 1%. In effect, this would be a universal income, but not designed to be liveable welfare.

In addition, I support cashing out the tax-free threshold with a universal refund for all adults including workers below the threshold and non-workers. Increasing this refund is a good way to provide general compensation, such as for the GST or a carbon tax, or for disbursing mining royalties. It’s clean, and to me preferable to complex manipulation of welfare benefit and tax rates.

(Perhaps these universal income schemes may grow to enough to live on, with categorical welfare benefits needed only as supplements. Maybe, one day, they morph into a genuine UBI. It seems unlikely to me, but the massive welfare states that emerged by 1960 would have seemed unimaginable and delusional to a normie in 1910. So who really knows? I think it would take a global black swan or two.)

Freedom from work

The plan above (excluding the UBI bit) doesn’t go all the way to the total freedom from labour that post-materialists might desire. But it is a big turn of the dial. Esping-Andersen is right to view freedom from market labour (basically what he calls “decommodification”) as a spectrum rather than a binary:

de-commodification should not be confused with the complete eradication of labour as a commodity; it is not an issue of all or nothing. Rather, the concept refers to the degree to which individuals, or families, can uphold a socially acceptable standard of living independently of market participation

Esping-Andersen 1990, 47

Short of robot communism, it’s hard to imagine a society with no significant incentives or social pressure to work. But under my system people would have more relative autonomy, less to fear from the sack. They could quit or reject work and take time out with much less risk of financial ruin. On the unemployment benefit, they would receive a pension-level payment – regardless of their assets or their partner’s income. Moreover, there would be a guaranteed minimum even if everything fell through. Full employment policy would facilitate re-entry into employment.

The universal dividend and universal refund would assist people to reduce their work hours or take breaks from work. Full employment policy, combined with union pressure and strong welfare, would pressure employers into accepting more flexible working hours and conditions. And though the system wouldn’t be designed to facilitate indefinite discretionary exit from employment, people will no doubt find a way to undertake their private projects around the cushy job search requirements. Anecdotally, this was a common strategy for artists and musicians prior to the incessant intensification of conditionality in the mid-1990s, particularly under Howard’s Mutual Obligation policy. In my model people would explicitly be allowed a period to experiment with arts production, after which normal (relaxed) job search requirements would kick in, which would still allow a lot of time for personal projects even if it was not an official objective. I think more scope for this would be positive and healthy for society.

Freedom from male breadwinner model

Australia’s industrial relations and welfare system has traditionally been built around a male breadwinner model, famously codified in the Harvester Judgement. The landmark judgement set award wages for men to include wife and child dependencies. Australia’s welfare system was largely built around this logic, with wives to rely on husbands, including in unemployment and disability, before the state. While gender is no longer explicit, the breadwinner dependency rule effectively remains and in practice is highly gendered.

My proposed system would instead provide most benefits as an individual right, dramatically increasing freedom from dependency on families, “defamilialisation” in Esping-Andersen’s lexicon. The state should not completely outsource responsibility for living expenses of people with disabilities or unemployed people to their loved ones. It places these people in a degrading and vulnerable position, without autonomy, often reinforcing traditional gender roles. It can also be a significant impost on the partner and family, a tax on love. Societies have superior capacity to risk pool than do households – we should use it.

(It’s worth noting that even in a family-dependency model, the government should still contribute to the cost of dependencies. If the system is relying on breadwinners to pay for dependencies as a social obligation, then under the ability to pay principle they should have lower tax. This recognises that equality depends not just on income (“vertical equality”), but on how that income has to spread out over different numbers of people with differing needs (“horizontal equality”). Horizontal equality is a mainstream priority in tax policy, and it’s why many countries, including Australia until recently, have had tax concessions for dependent children and spouses. Of course Australia has become defamilialist on taxes, while remaining familialist on payments! The only coherent factor is cherry picking whatever ideology is best for the budget.)

Critical to defamilialisation is, perhaps counter-intuitively, universal child benefits, also known as family benefits. Means tested schemes withdraw benefits with income, thus reducing incentives to work just like a tax. This produces high “effective marginal tax rates” (EMTRs) on households with children somewhere in the middle of the income distribution (in Australia, households with low to middle equivalised household incomes). The withdrawal has an added perversity, as the great Patricia Apps has tirelessly shown. Because it is based on combined income, it is effectively a joint income tax regime, also known as “income splitting”. This subjects secondary earners, usually women, to a high EMTR based on the income of their partner. The effect is to discourage women’s labour force participation.

Efficiency, simplicity and equity of access

Means testing child benefits is also inefficient. It assigns high implicit marginal tax rates precisely to the group that is most responsive to them – second earner women – resulting in more distortions and weaker work incentives than under a universal system combined with higher income taxes. This intuition has been corroborated with modelling recently published in the Australian Economic Review (written up here).

A budget neutral tax switch to repeal the job killing FTB A quasi-tax is a high priority. It unites neo-classical tax reform with universalist and feminist objectives. It unites equity and efficiency.

Finally, a universal child benefit ends the current mess of form filling and income estimation that creates barriers to claiming. Every form is barrier. It creates child poverty in vulnerable families whose parents fail to understand or complete the required administration. The income estimation leads to debts, particularly in families with unstable incomes. Debts hurt battling families the hardest. We should also end the egregious vaccination conditionality. Poor kids shouldn’t be punished with poverty for the bad choices of their parents.

I have argued the case for a universal age pension elsewhere.

All of the above is, I believe, achievable over the long run. The Age Pension reform is a lower priority from a social justice perspective, and should advance in a tax reform context on neo-classical efficiency grounds. Institutions like Treasury, PC, Grattan etc have to be persuaded to put aside their “budget guardian” hat and put on their “economic efficiency” hat. It’s hard to imagine a steep, narrow-based, distortionary wealth tax on middle class non-housing assets being tolerated in any other context. Like most people, policy economists and bureaucrats operate through heuristics, rules of thumb which are not always rational. In this case the heuristic is to adopt a budget sustainability frame when it comes to spending, and an economic efficiency frame when it comes to tax. (This is not to assert these groups necessarily support the Age Pension assets test in its current form, but I believe more effort and emphasis would be placed on it if it was legally a tax. But I also believe they can be persuaded.)

The spending (and taxes) required for welfare measures above would be large (over $100 billion), but this is much lower than a UBI and a very large share of it is lower priority age pension universalisation. We can work towards the package incrementally.

Basic income ideals – cash, unconditionality, universalism, a basic minimum and payment as an individual right – can be delivered through a web of payments backed by a guaranteed minimum. I am optimistic we can achieve a functional basic income and believe advancing the social democratic welfare state model is the most feasible way of doing it. It is a vision that unites social justice and efficiency, one that empowers us to engage with economic risk knowing that we have protection, operating in synergy with full employment policy. It modernises social protection built in a male breadwinner era to recognise the reality of dual income families today. It curtails the dominance of market labour in our lives, while also enabling us to enter or exit partnerships and families without losing our individual economic autonomy. And it provides practical, salient cost-of-living support to a broad spectrum of Australian individuals and households, recognising the varying cash flow needs all of us experience as we go through life.